In the U.S., we send our 5- and 6-year-olds to kindergarten classrooms across the country so that they can grow, learn, and become the future leaders of tomorrow.

Teachers bear a heavy responsibility to train the next generation, and sometimes teaching a class isn’t as straightforward as it can seem. Every day, teachers straddle the line between equality and equity in education. That is, providing students the same education as opposed to providing students an education in the specific personalized way they need it.

Equity is defined by the Glossary of Education Reform as encompassing a “wide variety of educational models, programs, and strategies that may be considered fair, but not necessarily equal.”

While public school is available for all students who reside in a district, certain kids need more than others to succeed, due to a disability or an inequality in the student’s life, such as income inequality. Providing more equity in education levels the playing field for students who start from behind compared to others.

During President Barack Obama’s tenure in office, the Department of Education offered grants to help promote equity in education.

Equality vs. Equity: A Matter of Enough

Equity and equality are important for student success in different ways.

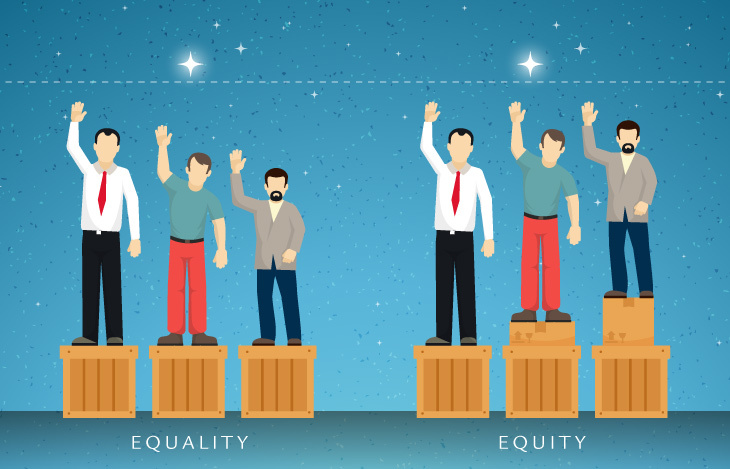

Equality denotes how people are treated, such as providing students an equal amount of respect or an equal amount of instruction. But equity, on the other hand, is about giving each students the tools he or she specifically needs to thrive.

Some students need additional individual attention from educators in order to fully understand a concept, and even more broadly, many students have different learning styles. Some students prefer learning by voice (audio) while others are more visual learners. Others are tactile learners, preferring a hands-on approach.

And outside of the learning environment, some schools fail to provide equitable education to their students because of a student’s socioeconomic situation, or how the student’s home life is.

Cases of Student Inequity

Decades of research have found that the first five years of a child’s life are crucial for brain development. Children who begin learning at a young age, whether from parents reading to them, learning alphabet letters or how to identify zoo animals, have a head start compared to students who weren’t afforded that privilege growing up.

For example, we can look at a case of two five-year old children. One student had access to books before kindergarten and another didn’t. Since the former student received a head start in his reading comprehension and vocabulary from his or her parents before entering traditional education, the latter student will likely be starting from behind when he or she enrolls.

Similarly, a research paper by Sean F. Reardon of Stanford University titled The Widening Academic Achievement Gap between the Rich and the Poor showed that students who attended preschool prior to kindergarten performed better than those who didn’t. With the lack of early cognitive development, students who didn’t attend preschool come to kindergarten with a disadvantage.

Another example of student inequity is when a student is living near or below the poverty line.

Reardon found the gap is widening between students raised in households with incomes in the 90th percentile of the family income distribution to households with incomes in the 10th percentile.

Compared to data from the early 1940s, Reardon found that the income achievement gap between the 90th and 100th percentile students born in 2001 increased to around 75 percent, with steady growth widening the gap since the mid-1970s.

In addition, it’s common that households around the poverty level have parents who are struggling to pay bills, and they may have to work long hours that prevent them from placing an increased focus on their children’s academic future.

The recent boom of technology in classrooms across the country is also another example of student inequity.

While many schools across socioeconomic levels have been able to provide tablets, laptops or other electronic devices to students, there are some schools that have yet to provide this technology to their students.

Technology gives students the opportunity to learn even when they’re away from the classroom. They can learn by viewing a PowerPoint presentation, or video via Blackboard or another program. Teachers can even ‘flip the classroom,’ which has students first review a lesson at home and then working on what they learned in class the next day.

But students without access to technology could be left behind.

Lastly, there are examples of discrimination against certain students that could hold them back and fail to help them reach their potential. In some cases, minority students are discriminated against and not provided with the equity they may need to succeed.

Bridging the Gap

Between 2009 and 2018, several federal initiatives were rolled out in the interest of bridging academic inequity. Here are a few examples:

- Title I: This formula grant program provides financial assistance to local education agencies (LEAs) and schools with high numbers or high percentages of children from low-income households to ensure that the students meet challenging state standards.

- IDEA: The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act of 2004 (IDEA) “authorizes formula grants to states and discretionary grants to institutions of higher education and other nonprofit organizations to support research, demonstrations, technical assistant and dissemination, technology, and personnel development and parent-training and information centers.”

- Promise Neighborhoods: This discretionary and competitive grant program provides funding to support nonprofit organizations, including faith-based nonprofits, institutions of higher education, and Indian tribes in order to give all children growing up in “promise neighborhoods” access to great schools and community support.

- Investing in Innovation: This grant program provides funding “to support LEAs and nonprofit organizations in partnership with one or more LEAs or a consortium of schools.” The grants are set to be awarded to schools with a record of improving student achievement and attainment with innovative practices, among other qualifications.

Veteran teacher Shane Safir has developed a series of strategies to provide more equity in the classroom.

- Know every child: When a teacher gets to know all of his or her students, the teacher can learn what learning style works best with the student and help them reach their potential.

- Become a warm demander: Have high expectations of your students, but also back that up with a commitment to every student’s success.

- Practice lean-in assessment: As teachers get to know their students, they can begin to put together their student’s learning story; i.e. how he or she approaches tasks, what his or her strengths are as a learner, and what the student’s struggle with.

- Be flexible with routines: Be willing to “flex” or set aside your class-wide plans to focus on individual instruction.

- Make it safe to fail: Usually, when a child fails a test or feels shame about a grade, he or she will either sit quietly or act out with bravado. In an equitable classroom, provide an atmosphere where it’s okay to fail and make mistakes.

- Culture is a resource: Take advantage of each of your student’s individual cultures. The differences among your students are to be celebrated and valued.

Make an Impact in Your Local School System

King University can help you achieve your professional goals, featuring small class sizes with knowledgeable faculty who have your success in mind.